Great Problem Solver

The Securitech Lexi series retrofit exit device trim is available with a variety of back plates and adapters that allow it to be used with most major brands, including many surface vertical rod and concealed vertical rod exit devices. Compatibility with a variety of vertical rod devices is a major plus.

The Securitech Lexi series retrofit exit device trim is available with a variety of back plates and adapters that allow it to be used with most major brands, including many surface vertical rod and concealed vertical rod exit devices. Compatibility with a variety of vertical rod devices is a major plus.

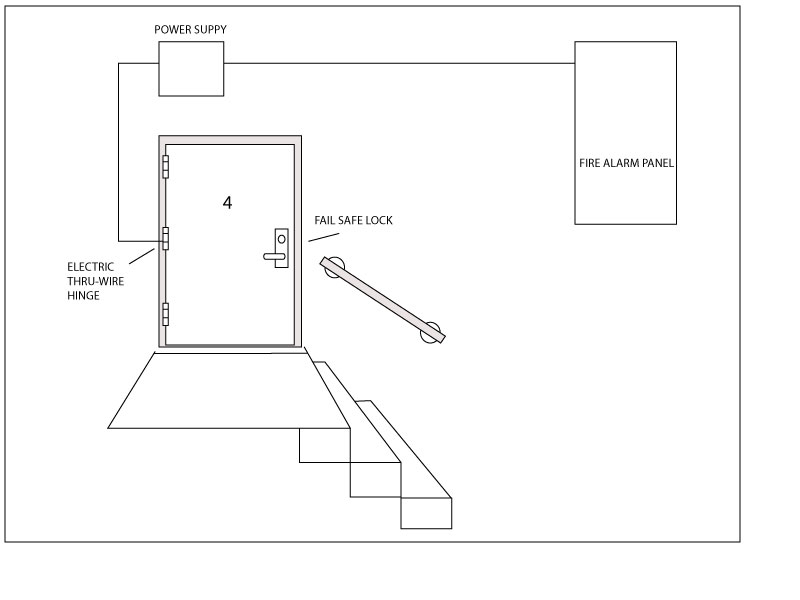

I mean, anybody can electrify a rim exit device by simply installing an electric strike. However, while it is possible to install an electric strike on a vertical rod device it rarely brings a good result. First of all, in order to use an electric strike you have to first lose the bottom rod. That just leaves one latch at the top of the door to provide all the security. If it is a tall door or a flexible door – like an aluminum storefront door – you can pull the bottom open several inches with just that top latch holding it. Add a little time and a little hinge sag and pretty soon you have no security at all.

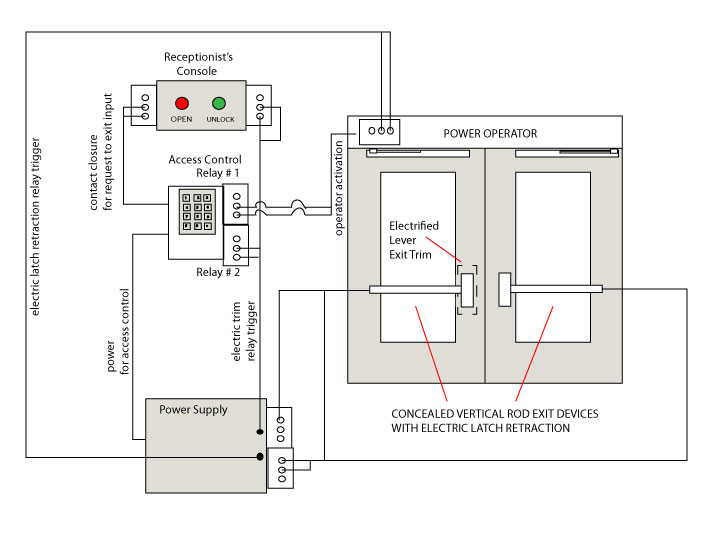

The other solution is electric latch retraction, or electric latch pullback, as some manufacturers call it: relatively expensive compared with a Lexi trim. Also, electric latch retraction is a fail secure only solution when locking trim is used and therefore may be inapplicable to fail safe installs such as stairwells, unless passage function (always unlocked) trims are used.

I notice that right out of the box the Lexi is very self contained. Other than a tiny box containing mounting screws, tailpiece operators, and a cylinder collar and cam, what you see is pretty much what you get. It’s pretty hefty for its size – it is designed on the slim side so as to be usable on narrow stile as well as hollow metal or wood doors. This does mean that the installer may have to be a little creative when replacing a larger exit device trim with the Lexi.

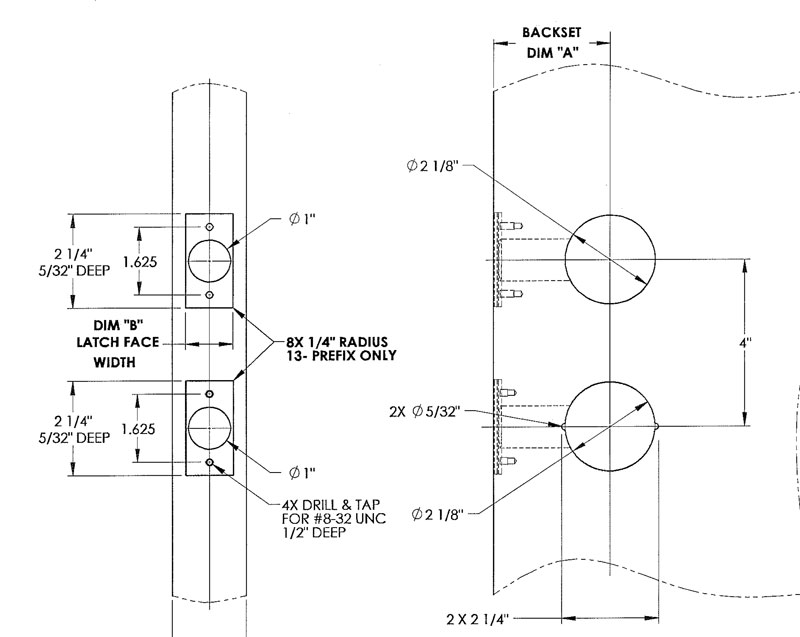

Installation instructions are easy to follow and short – only four pages, including the template. Something I would have liked to see in the instructions, but didn’t, was current draw. If I am installing one of these, the number of amps it draws are not going to matter much to me. But if I am installing twenty of them and want a centralized power source, now it’s an issue. Yet it isn’t anything that an experienced low voltage specialist with a ammeter can’t find out in two seconds.

Installation instructions are easy to follow and short – only four pages, including the template. Something I would have liked to see in the instructions, but didn’t, was current draw. If I am installing one of these, the number of amps it draws are not going to matter much to me. But if I am installing twenty of them and want a centralized power source, now it’s an issue. Yet it isn’t anything that an experienced low voltage specialist with a ammeter can’t find out in two seconds.

One of the great innovations I noticed right away is the rotation restriction clip that allows the installer to customize tailpiece rotation to the exit device. I do not think that this is handled better by any other manufacturer. Correct degree of rotation often determines whether a trim will work or not, and to have a trim that has degree of rotation so easily selectable is damn nice.

As mentioned in the sales literature, since Securitech’s Lexi trim is compatible with so many exit devices, if you have a facility with different brands of exit devices dispersed throughout, you can install access control and unify the exterior appearance at the same time. And in addition to being versatile it is also durable. Forcing the lever only causes its internal clutch to break away, and it can easily be set right by rotating it back the other way.

As mentioned in the sales literature, since Securitech’s Lexi trim is compatible with so many exit devices, if you have a facility with different brands of exit devices dispersed throughout, you can install access control and unify the exterior appearance at the same time. And in addition to being versatile it is also durable. Forcing the lever only causes its internal clutch to break away, and it can easily be set right by rotating it back the other way.

All in all the Securitech Lexi trim seems to be a well built, versatile problem solver. I think you’ll find it useful in many access control installations.