Definition

Basically:

- Fail Safe = power off, it’s unlocked

- Fail Secure = power off, it’s locked

Electric locking devices include:

- Electric strikes

- Electromagnetic locks

- Electromechanical locks

- Electrified exit devices

Most electric strikes are sold fail secure by default. For example,

if you order a Von Duprin 6123 24V US32D, and architectural grade 1

electric strike, it will most likely come fail secure regardless if

it has Von Duprin’s “FSE” (standing for fail secure) in the part number

or not. The part number in the Von Duprin price book does not include

“FSE.” To be sure you are going to get a fail safe electric strike (not

the norm) if that is indeed what you want, in this instance you would

include Von Duprin’s abbreviation for fail safe, “FS”, for example,

6123 -24V-FS-US32D.

All electromagnetic locks are fail safe because they are always

unlocked when disconnected from the power source. Using a battery

back-up does not make an electromagnetic lock fail secure because

the magnet would still be unlocked if the power was disconnected.

Later in this article it should become apparent why this detail

is important for reasons of life safety.

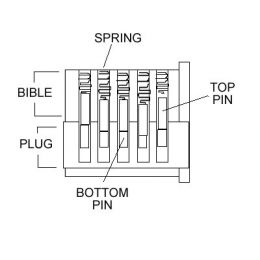

Electromechanical locks include standard cylindrical or mortise

locks that have been electrified and locks that are designed to

only work electrically, such as an electric bolt lock. They are

sold in equal amounts fail safe and fail secure.

Electrified exit devices come in a variety of functions, including

those with electric latch retraction and those with electrified outside

trim control. Electric latch retraction devices are fail secure whereas

exit devices with electrified exterior trim control might be either

fail safe or fail secure.

Application

Electric Strikes

Fail safe electric locking devices are used wherever doors must remain

unlocked in the event of a fire or other life safety emergency. If

the opening is fire rated, it must be positively latched by a fire

rated device in the event of a fire. Therefore there is no such thing

as a fire rated fail safe electric strike because if the power were

off (as it might very well be during a fire) the door would not be

positively latched. If you install a fail safe electric strike on

a fire rated opening, the inspector can require you to replace the

entire doorframe.

Technically, fire rated door frames cannot be modified in the field,

but must be prepared for hardware (including architectural grade electrified

hardware) in a fire rated shop. I have never heard of this being enforced,

nevertheless, the AHD (Authority Having Jurisdiction) could enforce

it, so if you plan to modify a fire rated opening in any way it might

be a good idea to get the local fire marshal on board during the planning

stages.

In general, a fail safe electric strike is a good choice for a “non-fire-rated

door that must be unlocked in the event of an emergency other than

a fire” kind of application.

Fail secure electric strikes are a good choice for exterior or other

non-fire-rated doors where remote release or electronic access control

is needed. They are pretty reliable, usually not difficult to install,

and relatively inexpensive. One of the chief disadvantages of an electric

strike is that, on out-swinging doors, they provide an opening into

which a burglar can insert a tool, such as a tire iron, to pry directly

on the locking device. A latch guard is a minimally effective deterrent

to this kind of attack.

(Exterior doors are almost never fire rated, and if they are, usually

it is because all the doors on the job were ordered to the same spec,

not because they have to be.)

Electromagnetic Locks

Some inspectors and fire marshals just don’t like electromagnetic

locks. This is another reason to get your local AHD on board from

the start. But if your AHD is not an obstacle, a mag can be a good

solution for existing fire rated doors with existing fire rated hardware

on them. The fire rated hardware can stay to keep the door positively

latched in the event of a fire, and the mag is inherently fail safe,

so it could be a good choice for stairwell doors, greatly simplifying

the application. The problem with mag locks is that they lock both

sides of the door simultaneously. That means you have to deal with

both a means to get in (access control) and a means to get out (presence

detector and redundant exit pushbutton, for example).

If the door already has an exit device, it is probably possible to

install a request-to-exit (RX) switch in the bar to allow exit by

a fully mechanical means – a factor which might make the AHD happier

with the installation. The AHD will also want to know that all electromagnetic

locks are wired so that the fire alarm will cut power to them in the

event of a fire.

Since a mag lock does not positively latch, it cannot be legally

used alone on a fire rated door. There must be a fire rated positively

latching mechanism in addition to the mag.

Delayed egress electromagnetic locks can also be used for access

control on egress doors while helping to prevent unauthorized exit.

For more information on delayed egress, please visit:

Electromagnetic locks are not too expensive and are very easy to

install. Because they are inherently fail safe, you may want to install

a battery back-up system so that they remain locked during routine

power outages.

Electromechanical Locks

Fail safe electrified standard locks are ideal for stairwell doors

(unless they already have exit devices) because they remain positively

latched when unlocked. Many states and localities require that stairwell

doors be unlocked in the event of a fire, and because all interior

stairwell doors are fire rated, they must also remain positively latched.

In order to replace a standard mechanical lock with an electrified

one, a raceway must be drilled through the door from lock side to

hinge side so that wire can be run to power the lock. If you guessed

that, technically speaking, this voids the fire rating on a fire rated

door, you were correct. Be sure to clear all modifications to fire

rated openings in advance with the local AHD.

Electric bolts are usually used as a last resort when no other application

will work, such as when retrofitting access control to automatic sliding

doors. Electric bolts are most commonly used in prisons, where egress

concerns are treated rather differently than commercial applications.

They can also be used in place of electromagnetic locks, however electric

bolts designed for commercial (rather than detention) applications

are less secure, less durable and more difficult to install than mag

locks.

Electrified Exit Devices

If a door has an existing exit device or an architect has specified

an exit device for an opening, it is because the capacity of the building

in terms of the number of people therein warrants the use of an exit

device. Therefore it is unwise to replace an exit device with another

kind of hardware.

Luckily, many exit devices can be electrified in the field either

by replacing internal parts of the device or by adding an electrified

trim (outside handle or lever).

As I mentioned earlier, exit devices can be electrified in one of

two ways:

- Electric latch retraction

- Electrified outside trim

Since electric latch retraction is always fail secure, it might not

be a good choice for stairwell doors unless it was always unlocked

from the stairwell side. If that were the case, the only probable

purpose for the electric latch retraction would be to unlatch the

door for a power operator (automatic door opener).

Electric latch retraction is ideal on exterior pairs of doors where

fail secure access control is required. Since exterior pairs of doors

are often equipped with concealed vertical rod exit devices, installing

electric latch retraction is often the easiest and best alternative.

Electric latch retraction (or electric remote dogging) is also very

compatible for use with power operators.

The down side of electric latch retraction, in addition to being

expensive in its own right, is that it often requires a special and

expensive power supply. Sargent 56 prefix exit devices are an exception,

requiring only a minimal power supply for activation.

Fail safe electrified exit device trim is a good alternative for

stairwell doors whether they already have an exit device or not. For

one thing, since the wire powering the trim is run through the exit

device, no modification of the fire rated door is necessary.

Electrified exit device trim is also available fail secure, and is

often a less expensive alternative to electric latch retraction where

simple access control is the goal.

Note on “Continuous Duty”

I have been asked, ‘What is the difference between fail safe and

continuous duty?’ Fail safe applies to the function of the device

as described above whereas continuous duty simply means the strike

is built to be constantly powered if so required. The confusion arises,

I think, because all fail safe locking devices are continuous duty.

This is because a fail safe device must have power to be locked. Fail

secure electric strikes that are connected to a timer and powered

all day to remain unlocked also must be continuous duty rated. Therefore,

not all continuous duty electric strikes are fail safe, but all fail

safe strikes are continuous duty.

Rule of thumb: almost every kind of electric locking device that

runs on DC current is continuous duty.