I often get a request to help create a system that locks people in. People want to lock children inside a daycare center, students inside a “Time-Out” room, babies inside a nursery in a maternity hospital or patients inside, for example, an Alzheimer’s disease in-patient facility for their own good.

I often get a request to help create a system that locks people in. People want to lock children inside a daycare center, students inside a “Time-Out” room, babies inside a nursery in a maternity hospital or patients inside, for example, an Alzheimer’s disease in-patient facility for their own good.

“Well, what if there’s a fire?” I ask.

That’s really the issue. If we are keeping them in, how are they supposed to get out in the event of a fire? Yet, except when there is a fire or other emergency that renders the building unsafe, it is in their best interest if they are kept inside.

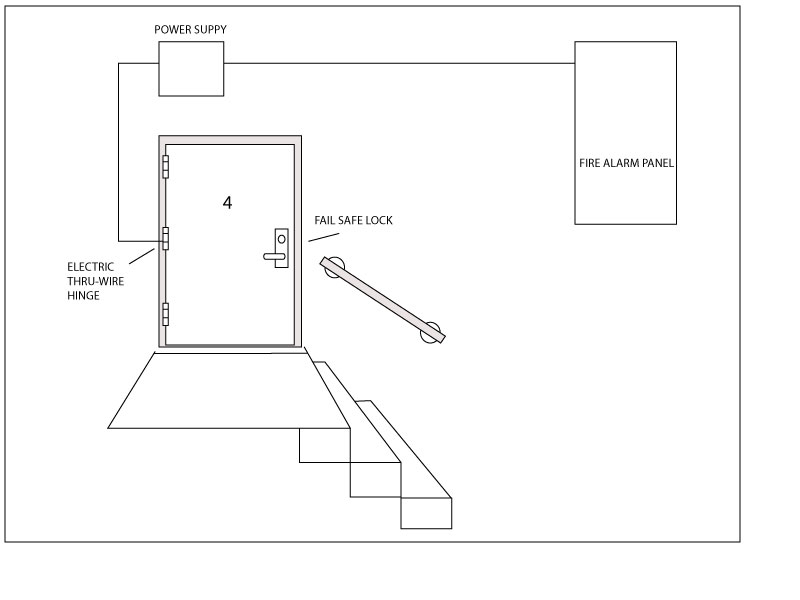

Often, people simply want to lock people in with an electromagnetic lock or other device. Since this is certainly a violation of life safety code, any injury that may result would be uninsurable and could invite litigation.

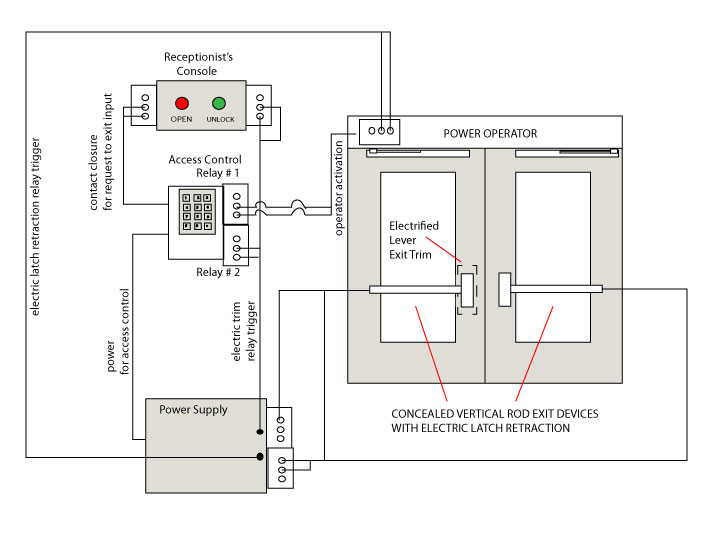

I discuss delayed egress systems in depth in another article (click here to read). A delayed egress system is really the right way to do this, since it is actually covered in the NFPA 101A Special Locking Arrangements section of the fire safety code, but it is fairly inconvenient to use. To get out without setting off an alarm users must use some kind of bypass request to exit switch like a keypad, card reader or key switch – much less convenient than, say, simply pushing a door open via the push pad on an exit device.

The gist of a delayed egress system is that, after a short ‘nuisance’ delay, the lock sounds an alarm for fifteen seconds and then lets the person out. That means that authorities on the secured premises have fifteen seconds to get to the exit and prevent unauthorized egress.

Where unauthorized egress is not a life threatening prospect, therefore, a delayed egress system is perfectly adequate. However, when a person’s life may depend on being kept inside their care facility, a more complex solution maybe required.

A great solution for Alzheimer’s or other dementia care facilities is the WanderGuard system by Stanley. This system is designed for Alzheimer’s and other health care facilities where unscheduled patient departure is an issue, and covers other needs with fall monitoring and patient call capabilities. Patients are fitted with bracelets that serve as tracking and communication devices. As one might expect, such a system is not inexpensive and a bit on the overkill side for use in a day care center or maternity facility. To physically keep people inside the facility, the WanderGuard system is designed to interface with delayed egress locks.

I think that the WanderGuard system would be a good choice for use in maternity ward nurseries as well.

The situation is more challenging when you have a day care center or a “Time-Out” room.

I had heard that Schlage was coming out with a mechanical time out lock, but a search as of today renders only the same Time-Out Room solution: An electromagnetic lock with a momentary pushbutton. The troublesome child is forced into a room, the door is shut, and then the teacher or other disciplinarian must physically press the momentary contact pushbutton to keep the magnetic locked locked. As soon as the teacher lets go, the child is free.

As long as the button is momentary, I have no problem with this idea. Should there be a fire or other life safety emergency, even if the teacher panics and runs away, leaving the child in the Time Out Room, the child will still be able to leave the room and exit the building.

The right way to prevent the kids in a daycare center from running out of the building and into the street without permission is with a delayed egress system. True, it may be cumbersome to punch in a code on a keypad or present a proximity card for authorized egress, but delayed egress systems can be easily deactivated for periods of time, say, for drop off and pick up. A delayed egress system is more expensive than, for example, an electromagnetic lock connected to the fire alarm system for safety. But if you run the scenario of a fire in your mind, the fire alarm interface to the electromagnet malfunctions, panicked children and day care providers flinging themselves against an illegally locked door, too crazed with fear to think – suddenly a delayed egress system makes a lot more sense.

There is really only one place you can really lock someone in, and that’s in a jail or prison. Otherwise there must be some provision to let them out – for safety’s sake.

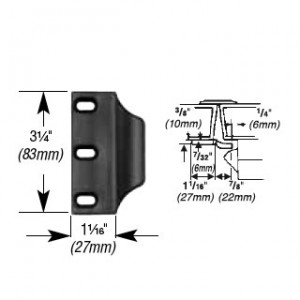

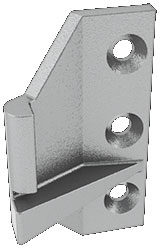

One of the hallmarks of bad hardware choices is the “pocket ripper” strike, used on a pair of doors when there is an inactive leaf with flush bolts or a vertical rod exit device and an active leaf with a rim exit device. Whenever I see this I think, “Cheap bastard,” because the only reason for this half fast solution is money and the desire not to spend it on doing the job right.

One of the hallmarks of bad hardware choices is the “pocket ripper” strike, used on a pair of doors when there is an inactive leaf with flush bolts or a vertical rod exit device and an active leaf with a rim exit device. Whenever I see this I think, “Cheap bastard,” because the only reason for this half fast solution is money and the desire not to spend it on doing the job right.