Overview

Almost all exit device manufacturers offer the option of electric latch retraction on their touch-bar style exit devices. Different manufactures may call it by other names such as ‘latch pull-back’ or ‘remote dogging’. Some people refer a device with electric latch retraction as an ‘electrified exit device’, but that could also refer to electric unlocking of outside trim – a different animal altogether. Electric latch retraction is accomplished by using a solenoid or electric motor to actually retract the latch or latches of an exit device.

Below are some characteristics of electric latch retraction:

- Electric latch retraction is fail secure. When power is supplied, the latches retract. When power is shut off, the latches extend, securing the door.

- Electric latch retraction works well with power operators because when the latches are retracted, the doors can swing free.

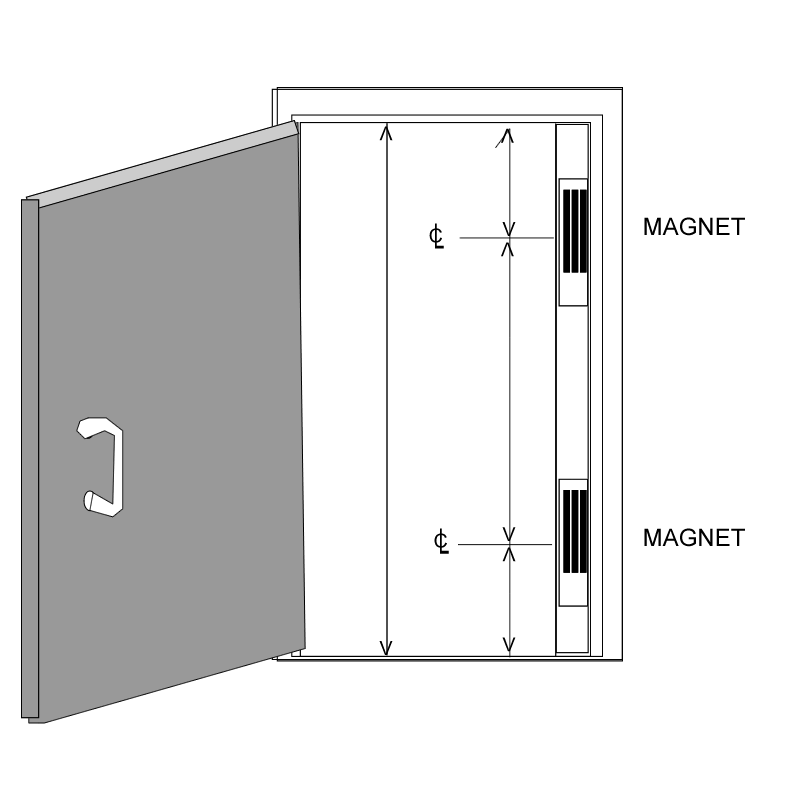

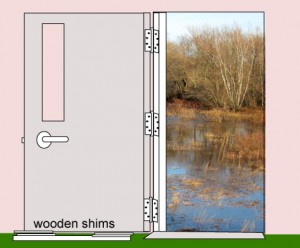

- With electric latch retraction, pairs of doors can continue to be latched top and bottom.

Cheaper alternatives, such as using an electromagnetic lock or an electric strike, would result in double doors that are only locked at the top. If they happen to be aluminum narrow stile doors locked only at the top, a person could actually pull the bottom of the locked door open several inches with very little effort. Such installations are at best sloppy, at worst not secure.

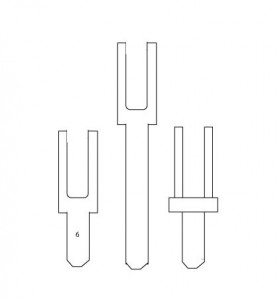

Solenoid vs. Motorized Latch Retraction

Solenoid driven electric latch retraction usually requires a specialized power supply due to the high inrush of current required (between 12 Amps and 16 Amps at 12 or 24 Volts DC). Motorized latch retraction generally requires just over 1 Amp of current for activation.

Solenoids are generally louder than motors, since solenoids move abruptly whereas motors retract at a slightly slower pace, and are therefore quieter.

Global Considerations

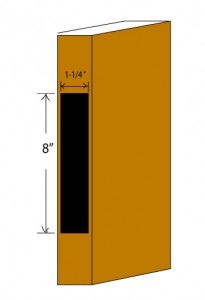

- Check door width. Electric latch retraction devices may not fit if the door is too narrow.

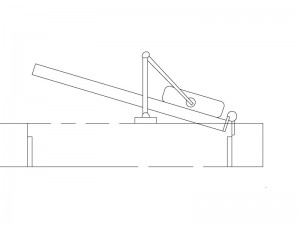

- A means of getting current from the door frame into the device, such as a door cord or electric power transfer will be needed.

- Voltage drop due to length of wire run could be an issue with high current inrush devices.

Following are examples of electric latch retraction exit devices by different manufacturers.

Please keep in mind that any of the part numbers shown may change without notice at any time.

Adams Rite

Adams Rite makes hardware primarily for aluminum-and-glass storefront type doors, but also for standard hollow metal and wood doors. All of their exit devices are available with MLR (motorized latch retraction) or solenoid latch retraction (EL for rim devices and LR for all other devices). They make rim, concealed vertical rod, surface vertical rod, and mortise exit devices.

- MLR motorized option draws 850 mA during retraction and 370 mA when maintained in dogged hold position at 24 VDC. Available in 24 VDC only. (ex. part number 8xxxMLR)

- EL solenoid driven option (for rim devices, example part number 8801EL-36-12) draws 1.5 Amps at 12 VDC and 600 mA at 24 VDC

- LR solenoid driven option (example part number 8xxxLR-36) draws 16 Amps at 24 VDC (inrush) and 500 mA (holding current) at 24 VDC

They do not offer a retrofit kit for field conversion of existing devices as of this writing, but aftermarket kits are available from other manufacturers.

Falcon / Doromatic

Falcon makes Doromatic exit devices primarily for aluminum storefront doors. All of their touch-bar style devices are available with electric latch retraction. Currently they use the Von Duprin-type solenoid for latch retraction, and use the Von Duprin PS914-2RS power supply to handle the 16-amp inrush current these solenoids draw.

The PS914-2RS will power up to 2 exit devices with electric latch retraction.

Doromatic offers a solenoid driven electric latch retraction field retrofit kit for their 1490 series concealed vertical rod and 1590 series rim devices as well as factory installed electric latch retraction. The EL1690 concealed vertical rod device and EL1790 rim device can be used field retrofit kits to electrify the 1990 and 2090 series crossbar “pipe-type” exit devices for latch retraction since they have the same latch side footprint and the vertical rod devices can use the existing rods.

Falcon offers their grade 1 series 24 and 25 exit devices with electric latch retraction or motorized latch retraction and field conversion kits.

Falcon exit device example part numbers:

- EL solenoid latch retraction (EL25-R-EO 3 US32D)

- MEL motorized latch retraction (MEL25-R-EO 3 US32D)

Example field conversion kits:

- ELK-3 or ELK-4 (or 650147 or 650148) solenoid latch retraction kit for 3- or 4-foot 24 or 25 series exit devices. Specify finish.

- 25-MELK-3 or 25-MELK-4 (or 47266630 or 47266631) motorized latch retraction kit for 3- or 4-foot 25 series devices only. 24 series MEL devices are factory only. Specify finish.

Precision

Precision makes exit devices for hollow metal, aluminum storefront, and wood doors, fire rated and non fire rated. All of their touch bar-style exit devices are available with electric latch retraction, and they offer both solenoid driven and motorized electric latch retraction for their grade 1 devices.

- ELR solenoid latch retraction (ex. part number ELR2103 630 36)

- MLR motorized latch retraction (ex. part number MLR2103 630 36)

Precision makes retrofit solenoid electric latch retraction kits specific to various device characteristics.

- Non-fire rated 3- or 4-foot wide stile exit device: ELRK-3 / ELRK-4

- Fire rated 3- or 4- foot wide stile exit device: ELRKF-3 / ELRKF-4

- Non-fire rated 3- or 4- foot narrow stile exit device: NELRK-3 / NELRK-4

- Fire rated 3- or 4-foot narrow stile exit device: NELRKF-3 / NELRKF-4

They make one kit to convert any of their touch bar devices to motorized latch retraction:

Sargent

Sargent offers a wide variety of exit devices in various functions and configurations to accommodate diverse applications. All 80-series models are available with “Remote Dogging / Latch Retraction”. Sargent recommends the Securitron BPS-24-1 power supply, a simple 1-amp, 24VDC power supply, to power electric latch retraction devices.

To designate Remote Dogging / Latch Retraction they use a prefix 56- to the exit device part number.

Example part number: 56-8810F 32D

Sargent offers two kinds of retrofit kits to convert existing Sargent exit devices to motorized latch retraction in the field. The R56A kit includes a complete touch bar (specify finish) whereas the M56A consists of a motor and control module unit that is unfinished. Rail size (according to door width) must be specified for either. Sargent uses letter designations for rail size:

- E = 24 to 32 inch door width

- F = 33 to 36 inch door width

- J = 37 to 42 inch door width

- G = 43 to 48 inch door width

Example part numbers:

- Modular kit: M56AF

- Push Rail Assembly Kit: R56AF 32D

Von Duprin

Von Duprin offers two kinds of electric latch retraction in rim, surface vertical rod, concealed vertical rod, mortise, and three-point exit devices for narrow stile aluminum storefront, standard hollow metal, and wood door applications. To order exit devices with latch retraction use prefix EL for solenoid latch retraction or QEL for motorized latch retraction.

EL prefix devices require the PS914-2RS power supply. PS902-2RS are the manufacturer’s recommendations for QEL prefix devices, but any regulated and filtered power supply 2 Amps or greater will do. If powering 2 devices simultaneously, the PS902-2RS will stagger the inrush, firing one QEL at a time. Since each draws 1 Amp, simultaneous activation of two devices might max out a standard 2 Amp power supply. If another manufacturer’s power supply will be used to power two devices, I suggest using a 3 Amp power supply.

Wire run/current drop factors apply.

Example part numbers:

- Solenoid latch retraction: EL99EO 3 26D

- Motorized latch retraction: QEL99EO 3 26D

Von Duprin offers a variety of retrofit kits to field convert existing exit devices to electric latch retraction. Options include motorized latch retraction kits, kits that include rail backplate (specify door 3 or 4 foot door width), kits with motorized latch retraction and hex key dogging, etc. Here I list part numbers for the most common variations:

- Solenoid Latch retraction (EL) kits:

- For 3-foot door width: 050070

- For 4-foot door width: 050078

- Motorized latch retraction (QEL) kits:

- For 3-foot door width: 958003

- For 4-foot door width: 040065

Dorma

Dorma offers solenoid and motorized latch retraction for their 9000 series exit devices. ES is the designation for solenoid driven latch retraction and MLR for motorized latch retraction. They offer full replacement touch bar and rail assemblies that can be used to field convert devices to ES or MLR.

Example exit device with latch retraction part numbers:

- With solenoid latch retraction: 9x00B RHR 630 ES

- With motorized latch retraction: 9×00 RHR 630 MLR

ES option requires Dorma PS501 power supply.

MLR option, Dorma DKPS-2A power supply recommended, but any 2 Amp regulated and filtered power supply will work.

Rail size designations:

- A – for door width 34 inches to 48 inches

- B – for door width 28 inches to 36 inches

- C – for door width 25 inches to 30 inches

Touch bar and rail assemblies, example part numbers:

- MLR option motorized latch retraction: MLRTBR 630 B

- MLR option fire rated motorized latch retraction: MLRFTBR 630 B

- ES option solenoid latch retraction: ESTBR 630 B

- ES option fire rated solenoid latch retraction: ESFTBR 630 B