The Medical Metaphor

As previously published in Doors and Hardware Magazine, Feb. 2016

As previously published in Doors and Hardware Magazine, Feb. 2016

As in the medical profession, correct diagnosis of door hardware problems is wholly dependent upon the knowledge, skill and powers of observation of the person whose job it is to correct the problem. “The devil is in the details,” they say, and it is never truer than when said in reference to doors and hardware.

Another old saying, “ignorance is bliss,” can be liberally applied to who those innocent building occupants and visitors who think that the answer to a lock that is not latching is to slam it until it does – or until the hardware falls off, whichever comes first. Yet by the same token, door hardware technicians who fail to look at door hardware problems holistically are equally blissful. If you have ever seen the latch hole in an ANSI strike enlarged to include half the head of the bottom mounting screw in order to remedy what is clearly a hinge problem you will understand what I am talking about.

The above occurs because the technician sent to solve the problem is guilty of treating the symptoms while failing to diagnose the disease. He or she observes that the latch is making contact with the strike too low to drop into the strike hole as it should, but does not question why this is happening. This example is a simple one, but the principle applies to more complex problems as well.

Method

A great way to make sure you correctly identify a door hardware problem on the first visit is to have a consistent method of examining the total opening. An example follows:

- If possible, speak with the person who has reported the problem, or better yet, meet with them at the opening so that they can show you what the problem is.

- As you approach the door, visually check the gap around the edges of the door on the top and both sides. (The gap should be one-eighth inch.) If the gap is greater in one place and less in another, the problem may be a bent hinge or misaligned frame.

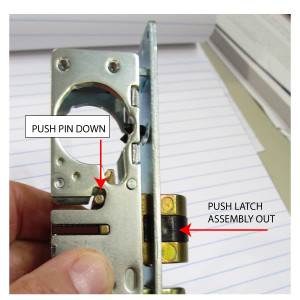

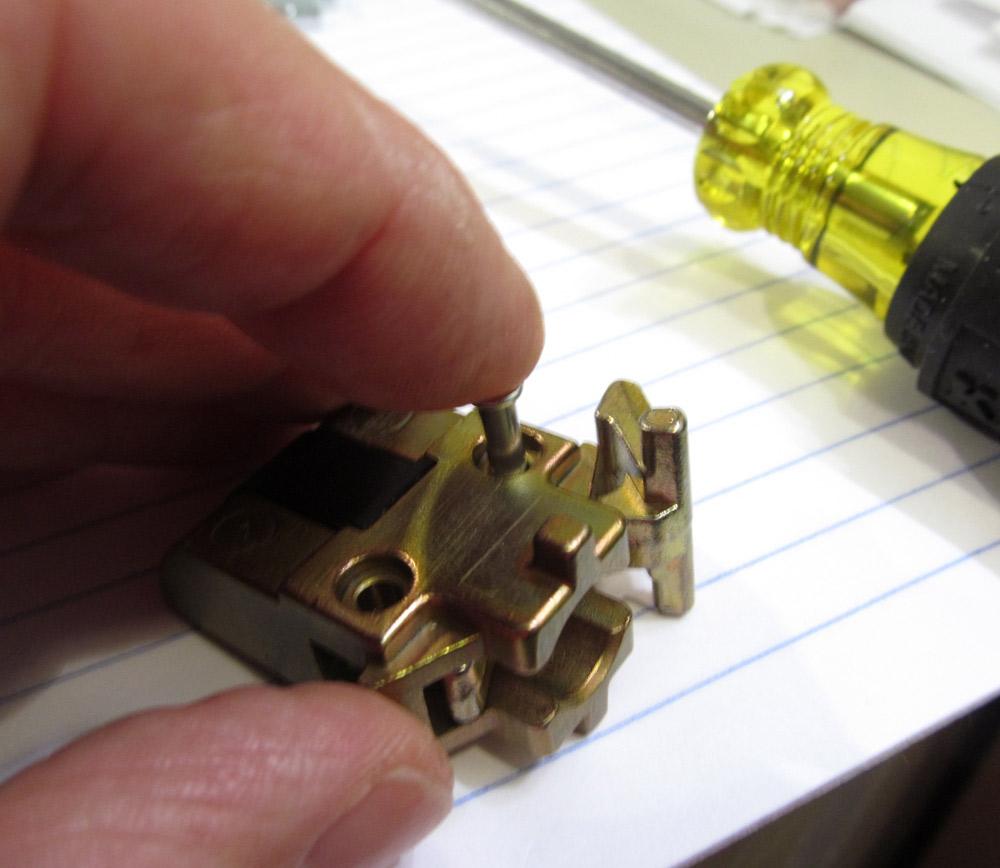

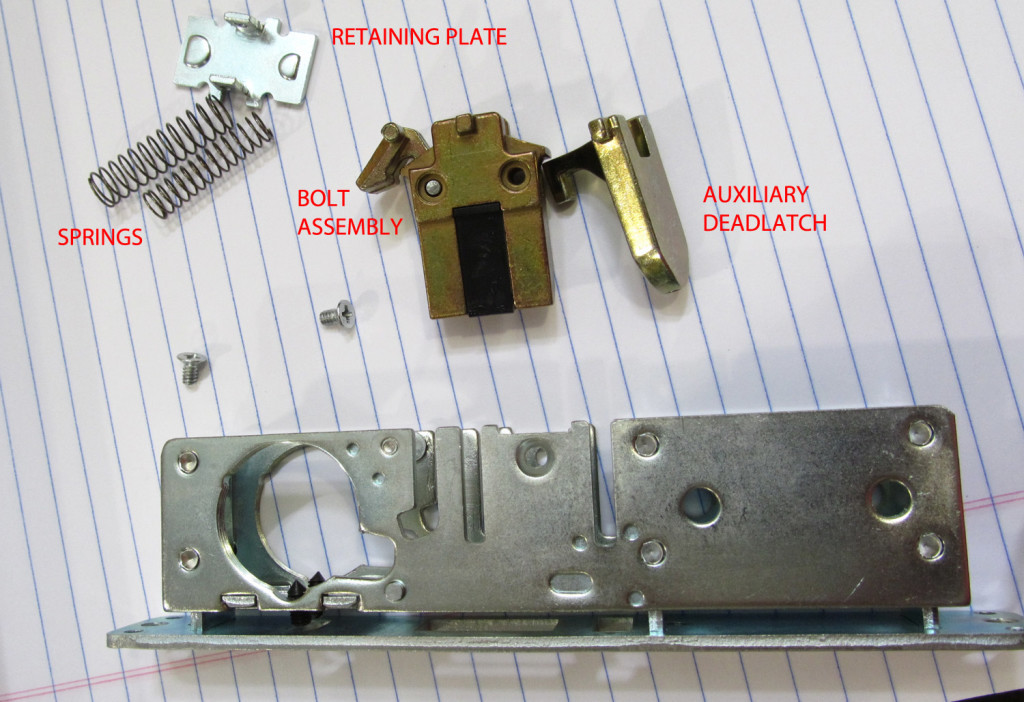

Open the door. How does it feel? Does the door itself stick? If it has a latch, is there resistance when you turn the lever to retract it? Do the hinges groan or squeak? - Inspect the door for dents and abrasions. For example, scratches at the top of the lock-side edge may indicate bent or loose hinges. Dents may indicate attempted forced entry: check for damage to internal lock parts. A dent in the gap between the door and frame above the top hinge may mean an object was placed there. The frame may be damaged and/or the top hinge may be bent.

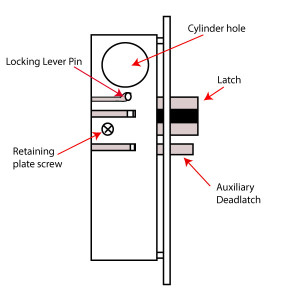

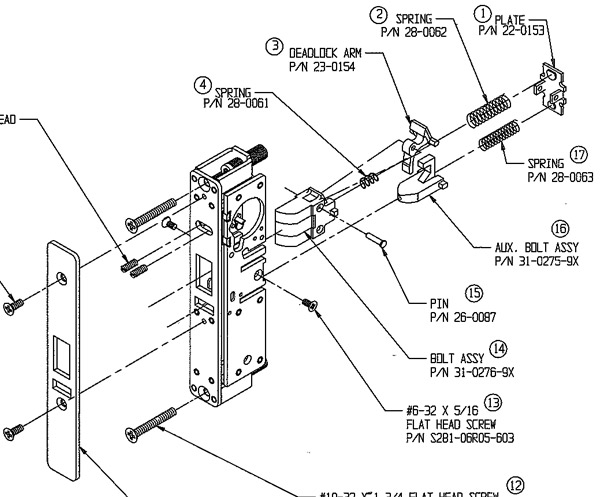

- Inspect the hardware for damage, missing parts and/or wear. If it is a hollow metal frame, are the silencers installed? If there are no silencers the door will not align properly and the lock will not latch correctly. Is the door closer leaking? Does the door closer arm move smoothly? Are the hinge screws all present and accounted for, and are they tight? If there is a latch, there probably is a drag mark on the strike. Does the drag mark reflect correct alignment?

In other words, look at the door, the frame and the hardware thoroughly and completely, and always do it the same way. That way you won’t fix one problem just to return the following week to fix another problem that you missed.

Tools May Be Required

To identify a door hardware problem you may find it helpful to use instruments or tools. For example, a carpenter’s level can help you determine whether a door or frame is level or plumb quickly and accurately, and a carpenter’s square can show immediately if the frame is true or sprung. A tape measure may be helpful to check if hardware is correctly located, whether or not the gap between door and frame is consistently one-eighth inch, and if one leg of the door frame seems to be longer than the other.

One problem most swiftly identified using a carpenter’s level is positive pressure. If you detach the closer arm and tape back the latch on a door that is level, and it swings open seemingly of its own accord, chances are it’s a positive pressure issue. Positive pressure occurs when the air pressure inside the HVAC ducts is greater than the pressure outside, causing air to be constantly forced out of the structure. Positive pressure can be powerful enough to prevent a door closer from closing the door, and sometimes the only cure is when the HVAC technician changes the settings on the air circulation system.

The positive pressure issue is one of those door hardware issues that may require someone besides a door hardware technician to fix.

Waiting For The Electrician

Problems with electro-mechanical and electronic locking systems, like positive pressure issues, may require a low voltage or electronics specialist to solve in addition to a door hardware technician. For liability reasons it is important to use technicians who are appropriately licensed as required in your locality.

Often these problems are due to mechanical as well as – or even instead of – electrical or electronic issues. Therefore the best situation for electronic or electrical door hardware triage is when the technician called upon to fix a problem is skilled in all three disciplines. Out in the world we are finding locksmiths that have their low voltage electrical technician license and a working knowledge of how to troubleshoot or program an access control system, systems integrators who can disassemble and repair a mortise lock, and even electricians who can adjust a door closer or repair an exit device.

This is a phenomenon driven by a market that desires to have one technician who can do everything, both for convenience and economics. In any event, a technician equally skilled in these areas solves the problem of cross discipline communication. If you’ve ever had to explain the difference between fail safe and continuous duty electrified door hardware to someone who just does not get these concepts you will understand what I’m talking about.

For this reason alone it behooves one in the door hardware repair and installation business to learn as much as they can and get all the credentials they need to be able to service all the door hardware out there in today’s electric and electronic world.

Closure

The age of door hardware in which we work today is the age of the renaissance woman or man, student of many skills. However, diagnosing the often complex ailments of doors and door hardware takes more than skill and knowledge: it requires mindfulness, openness, resourcefulness and humility. It is not only necessary to know what could go wrong (and doubtless will, according to Murphy’s Law); it is necessary to be aware enough to observe all the symptoms, to be open to all possibilities and to be imaginative in creating solutions. One must also have the humility to realize that it is not possible for anyone to know absolutely everything. Sometimes the most useful tool at your disposal is your mobile phone. A call to factory tech support can often save hours of fruitless aggravation.

No man is an island – but some men belong on one.