As seen in Doors and Hardware Magazine.

Whenever something is invented, humans find more uses for it. This is certainly true for door automation and electric locking. It was not long after people realized a door could be unlocked remotely using an electric strike and a door could be opened automatically using a power operator (automatic door opener) that they began using these devices together. Of course this combination of devices was soon interfaced with intercoms. Exit devices with electric latch retraction and electromagnetic locks were thrown into the mix, as well as access control, delayed egress and/or security interlock systems. Any of these systems alone is sufficient to complicate an installation, but when you start to use several on one opening, that’s when things really start to get interesting.

A hospital can be one of the best places to run into a doorway that needs to perform many functions (pun intended). Hospitals seem to have more varied reasons to keep different people out at different times, or to let them in or out by different means. In addition to standard life safety and security issues, hospitals also have to anticipate the needs of patients who may be under the influence of medication and/or mental disorders and/or have physical limitations. Some patients must be kept inside for their own safety while all patients must be able to exit swiftly and safely in the event of a fire.

Let’s use as an example a hospital emergency ward entrance used primarily by ambulance drivers. The hospital wants only ambulance personnel and the security guard to be able to activate the power operator, and to control access by use of a remote switch operated by the security guard for the general public and an access code by hospital employees (other than ambulance personnel).

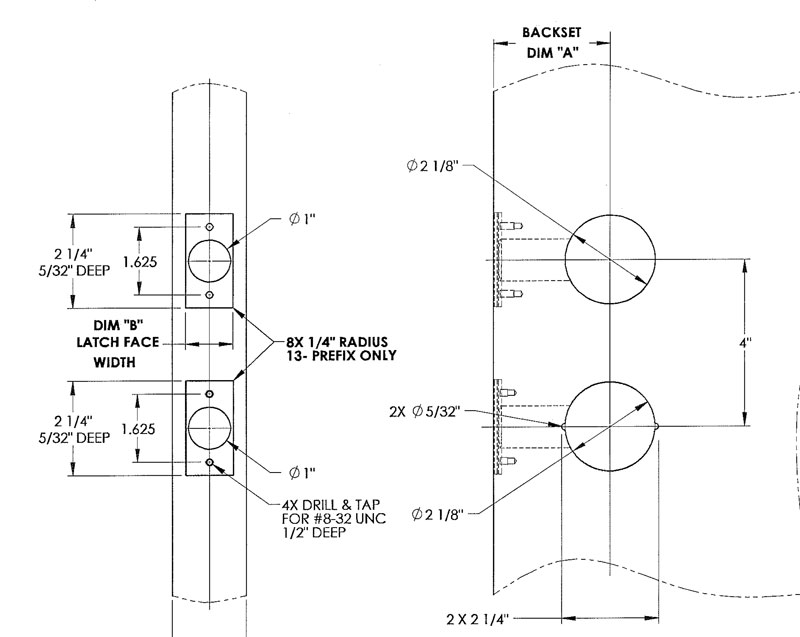

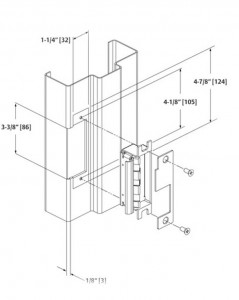

Since it is a pair of doors, concealed vertical rod exit devices are the most efficient, safe and secure way to lock them and provide reliable free egress in the event of an emergency. However, since there is a power operator involved, these devices must be equipped with electric latch retraction; and since use of the power operator was to be limited, a second electric means of opening the door would be required.

A simple way to solve the problem of the second means of unlocking is by using electrified exit device lever trim with one of the concealed vertical rod exit devices. Persons not requiring the power operator can get in by using the access control, or the security guard can “buzz” them in using one of two remote buttons. Because there will be two means of unlocking the door electrically, the security guard will need a small desk unit with two buttons: one that activates the power operator and electric latch retraction and one that activates the electric exit device trim.

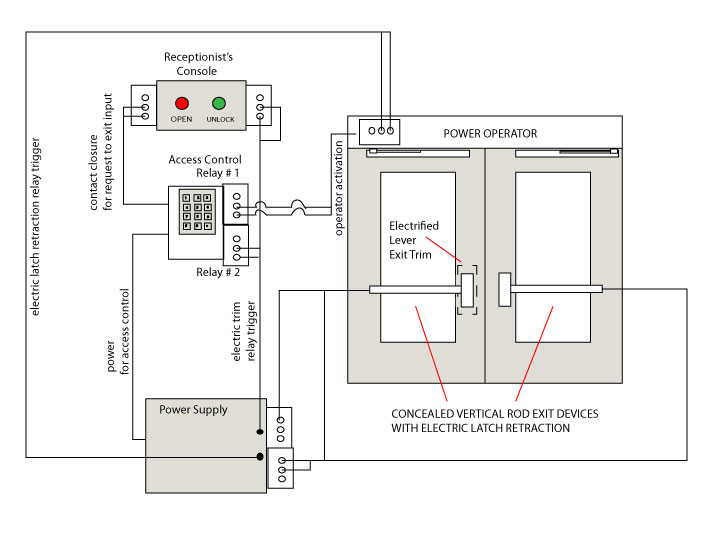

Below is an amateur wiring diagram (made by me) of how, basically, the system works.

Central to the concept is an access control device with two relays and a request to exit input. This allows several of the connections to be made through the access control system. If the access control system on site does not provide more than one relay, the same functions can be accomplished by using additional relays in the power supply.

The system as shown in my illustration above works like this:

Ambulance personnel activate the power operator using the access control system. The access control system signals the power operator via contact closure in Relay #1. The power operator triggers the relay in the power supply to retract the latches of the exit devices, then opens the door.

Other authorized hospital personnel use the access control system to unlock the lever trim. The access control system changes the state of Relay #2, triggering the relay in the power supply to unlock the trim. They turn the lever, pull the door open and walk in.

Injured people arrive on foot at the Emergency Room entrance. The Security Guard sees them (or is notified by intercom, not shown) and lets them in by pressing the red button, activating the power operator, or by pressing the green button that unlocks the exit device trim.

There exist many possible variations of this system. Knowledge of access control systems and door hardware are required, but the most important principal in play is the use of contact closure to signal multiple devices.